Become ROMANIAN

SPEAK LIKE A REAL NATIVE

AUTHENTIC ROMANIAN LIVING

From its formation in 1859 through the union of Moldavia and Wallachia to its modern development as a member of the European Union, Romania has played a pivotal role in European history. Its rich cultural tapestry reflects influences from Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian rule, blended with deeply rooted Romanian traditions. With its stunning architectural heritage, from medieval fortresses and painted monasteries to the iconic wooden churches of Maramureș, Romania offers a timeless journey through its dynamic and enduring cultural legacy.

After the fall of communism in 1989, Romania underwent a remarkable transformation. The nation embraced political and economic reforms, joining the European Union in 2007 and positioning itself as a dynamic player in Eastern Europe. Its thriving arts scene, expanding tourism industry, and focus on education and technology showcase a country that honors its past while forging a bright future. Today, Romania is a bridge between East and West, celebrated for its unique language, cuisine, folklore, and spirit of resilience.

We have created a selection of words and expressions that you won't find in any textbook or course, to help you become like a real native by understanding Romanian words that carry a deeper cultural meaning as well as expand your knowledge of the country and its history.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are interested in learning more about Romanian culture and history as well as the language, we recommend that you download our complete Romanian language course!

You will not only receive all the contents available on our website in convenient pdf or epub formats but also additional contents, including bonus vocabulary, more grammar structures and exclusive cultural insights with additional vocabulary that you won't in any other textbook.

The additional articles include specific words or expressions related to the culture of the Romanian and Moldovan people. Not only will you be able to speak the Romanian language with confidence but you will amaze your listeners thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.

BRÂNCUȘI

Brâncuși (Constantin Brâncuși) is regarded as one of the most important modernist sculptors of the 20th century and a central figure in Romanian and international art history. Born in 1876 in Hobița, Gorj County, he developed a unique artistic style that combined Romanian folk traditions with avant-garde principles. His works are characterized by simplicity of form, symbolic abstraction, and spiritual depth, making Brâncuși a pioneer of modern sculpture.

One of his most famous works is Coloana Infinitului (Endless Column), part of a monumental ensemble in Târgu Jiu dedicated to the memory of Romanian soldiers who died in World War I. Along with Masa Tăcerii (Table of Silence) and Poarta Sărutului (Gate of the Kiss), the ensemble reflects the themes of sacrifice, continuity, and love. These works are deeply tied to Romanian identity, while also being celebrated internationally as masterpieces of 20th-century art.

Brâncuși created a distinctive sculptural language by reducing forms to their essence. Works such as Pasărea Măiastră (The Maiastra Bird) and Domnișoara Pogany (Miss Pogany) reveal his interest in capturing spiritual purity and universal archetypes. His use of materials like wood, stone, and bronze reflects his mastery of traditional techniques combined with modern experimentation. The contrast between polished surfaces and raw textures became a hallmark of his style, influencing generations of artists.

Culturally, Brâncuși maintained a strong link with Romanian traditions. Elements of costum popular (folk costume), doina (lyrical folk song), and mituri românești (Romanian myths) appear symbolically in his works. Yet he was also deeply involved in the Parisian art scene, where he became associated with figures such as Marcel Duchamp and Amedeo Modigliani. His refusal to accept academic constraints and his pursuit of artistic independence established him as a defining figure of modernism.

The legacy of Brâncuși is both national and universal. In Romania, his name is associated with cultural pride, and his works are preserved in museums, monuments, and public collections. Internationally, his sculptures are displayed in prestigious institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. His influence can be traced in modern design, architecture, and abstract art.

BISERICA ORTODOXĂ

The Biserica Ortodoxă (Orthodox Church) is the dominant religious institution in Romania, shaping spiritual life, cultural identity, and national traditions for centuries. The majority of Romanians belong to the Biserica Ortodoxă Română (Romanian Orthodox Church), which is an autocephalous branch of Eastern Orthodoxy. Its central authority is the Patriarhia Română (Romanian Patriarchate), based in Bucharest, with the Patriarh (Patriarch) serving as the spiritual leader. The church has been a defining force in maintaining unity, especially during times of foreign rule or political upheaval.

Throughout history, the Biserica Ortodoxă played a crucial role in education and literacy. Monasteries served as centers of learning, where monks copied manuscripts and preserved religious and historical texts. The use of limba română (Romanian language) in liturgy was gradually consolidated, helping to strengthen national identity and distinguish Romanian Orthodoxy from neighboring traditions that relied on Old Church Slavonic. The church’s support of cultural figures, such as cronicar (chroniclers) and writers, made it an essential contributor to the development of Romanian literature.

Architecturally, the Biserica Ortodoxă has left a rich legacy through its monasteries, cathedrals, and parish churches. Distinctive features include frescoes, icoane (icons), and architectural styles such as stil brâncovenesc (Brâncovenesc style), which blend Byzantine influences with local traditions. Monasteries such as those in Bucovina are world-renowned for their exterior frescoes and are considered masterpieces of Orthodox art. These structures are not only places of worship but also symbols of endurance and resilience across centuries.

The rituals of the Biserica Ortodoxă continue to play a vital role in everyday Romanian life. Ceremonies such as botez (baptism), cununie (wedding), and înmormântare (funeral) mark the key stages of life, while annual celebrations such as Paști (Easter) and Crăciun (Christmas) blend Christian teachings with local folk traditions. The act of making the semnul crucii (sign of the cross) is a common gesture of devotion in both public and private spaces, emphasizing the presence of faith in daily routines.

Politically, the Biserica Ortodoxă has also held influence. During the medieval period, rulers relied on its authority to legitimize their reigns, while in modern times, it has remained an important institution in preserving continuity. Even under communism, when religion was restricted, the church maintained its role, though often under state pressure. After 1989, the Biserica Ortodoxă regained prominence, becoming a leading voice in social and moral debates.

CĂLUȘ

The Căluș (Căluș ritual dance) is one of the most distinctive Romanian folk traditions, recognized by UNESCO as part of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity. Practiced mainly in southern Romania, especially in Oltenia and Muntenia, the Căluș ritual combines dance, music, and symbolic gestures with strong associations to healing, fertility, and protection. It is traditionally performed during the period of Rusalii (Pentecost), when villagers believed that malevolent spirits, known as iele (fairies), could harm people and crops.

The performers, called călușari (Căluș dancers), are typically men organized into a group led by a vătaf (leader). They wear white costumes decorated with red ribbons, bells, and symbolic accessories such as sticks, which are used in their dances. The movements are energetic, acrobatic, and highly synchronized, often including leaps, kicks, and ritual gestures. The sound of the zurgălăi (bells) attached to their costumes adds rhythm and intensity, while the accompanying lăutari (folk musicians) provide music with fiddles, flutes, and drums.

The Căluș was believed to have magical and healing powers. Villagers called upon the călușari to cure illnesses or ward off bad spirits, and special rituals were performed for those who were sick or afflicted by the influence of the iele. The dance also symbolized fertility and agricultural prosperity, ensuring that fields and animals would thrive. In some communities, women were excluded from the group of dancers, but they were central to the ritual’s purpose, as the Căluș was often associated with protecting family health and household wellbeing.

The social dimension of the Căluș is equally important. The performance brought communities together, with villagers gathering to watch and participate. The jurământul călușarilor (oath of the Căluș dancers) was a binding ritual of secrecy and loyalty within the group, adding a layer of sacredness to their role. Breaking the oath was considered dangerous, as it was believed to attract misfortune.

Over time, the Căluș has become a national symbol of Romanian folklore. Ethnographers, musicians, and dancers have documented and preserved the tradition, ensuring its transmission to new generations. Today, the Căluș is performed not only in villages but also on stage by professional folk ensembles, serving as both cultural preservation and national representation at international festivals. Its endurance highlights the resilience of Romanian ritual practices, where ancient beliefs blend with community celebration. The Căluș remains a powerful expression of identity, linking spiritual protection, social unity, and artistic performance in Romanian culture.

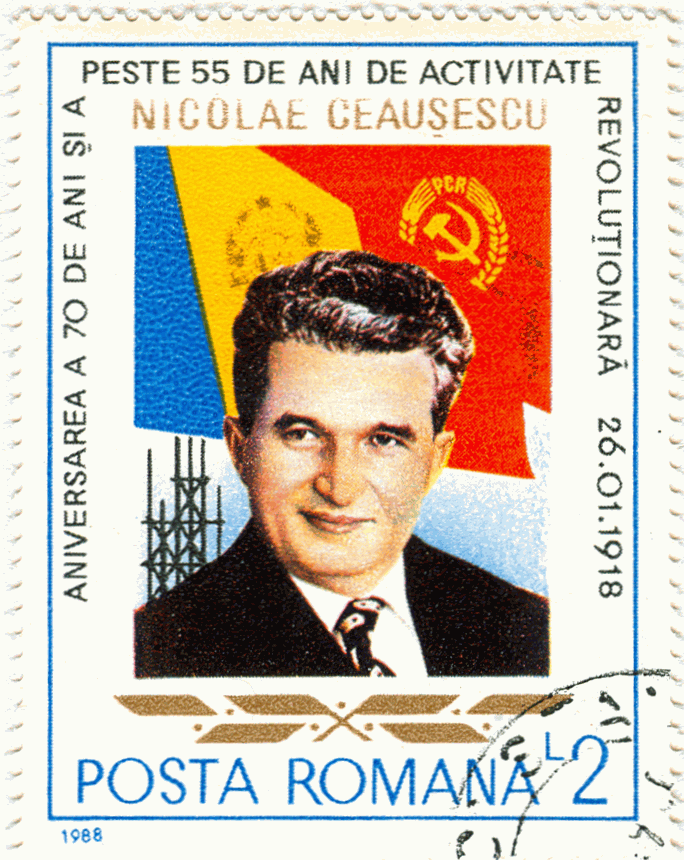

CEAUȘESCU

Nicolae Ceaușescu was the communist leader of Romania from 1965 until 1989, whose rule profoundly shaped modern Romanian history. As General Secretary of the Partidul Comunist Român (Romanian Communist Party), he consolidated political power into a highly centralized system, with himself and his wife Elena holding dominant roles in both state and party structures. Initially, his regime was marked by a relatively independent stance within the Eastern Bloc, earning some international recognition, but over time it became associated with authoritarianism, repression, and economic decline.

Under Ceaușescu, Romania pursued policies of industrializare (industrialization) and heavy investment in large-scale projects. This included the expansion of energy production, construction, and infrastructure. However, the drive for rapid development led to inefficiencies, poor resource allocation, and growing foreign debt. To repay external loans, Ceaușescu imposed harsh austerity measures in the 1980s, resulting in shortages of food, electricity, and basic goods for the population. The state promoted an official ideology of omul nou (the new man), aiming to reshape Romanian society according to communist ideals.

Politically, Ceaușescu created a personality cult, with extensive propaganda portraying him as a visionary leader. His speeches were broadcast constantly, and portraits of him and Elena Ceaușescu were displayed in public spaces, schools, and workplaces. The Securitate (secret police) became a powerful instrument of control, monitoring citizens, suppressing dissent, and instilling fear across society. Despite the repressive environment, some intellectuals and workers protested against the regime, though these acts were often met with swift punishment.

One of the most controversial aspects of his rule was the program of sistematizare (systematization), which aimed to modernize villages and towns by demolishing traditional houses and replacing them with standardized apartment blocks. This policy caused widespread cultural and social disruption, as centuries-old communities and architectural heritage were destroyed. The most notorious construction project of his era was the Casa Poporului (Palace of the People), a massive building in Bucharest that remains one of the largest administrative buildings in the world.

The regime ended with the Revoluția din 1989 (1989 Revolution), a popular uprising triggered by years of hardship and repression. Demonstrations in Timișoara spread across the country, culminating in mass protests in Bucharest. Ceaușescu and his wife were captured, tried by a military tribunal, and executed on December 25, 1989. Their fall marked the end of communism in Romania and the beginning of democratic transition.

Today, Ceaușescu remains a controversial figure. Some remember him for attempts at asserting Romania’s independence from Soviet control, while most associate his rule with repression, poverty, and the curtailment of freedoms.

COLINDĂTORI

The ceata de colindători (group of carol singers) is a central element of Romanian Christmas traditions, deeply rooted in both religious and folk practices. A ceată is usually formed by young men, though in some regions girls and children also participate, and they go from house to house during the period of Crăciun (Christmas), performing colinde (carols). These songs carry themes of birth, renewal, prosperity, and blessing, blending Christian symbolism with older pre-Christian motifs.

The structure of the ceata de colindători is organized, often with a vătaf (leader) who guides the group, assigns roles, and ensures discipline. The singers wear elements of costum popular (folk costume), sometimes decorated with brâu (belt) or căciulă (sheepskin hat), and carry symbolic objects such as bâte (sticks) or steaua (star), which is particularly associated with Christmas carols about the Nativity. Each household welcomes the group, and in return for their singing, the carolers receive gifts such as colaci (festive bread), apples, nuts, or small amounts of money.

The repertoire of a ceata de colindători includes different types of colindă. Religious carols focus on the Nașterea Domnului (Birth of the Lord), while others preserve ancient agrarian motifs, wishing for good harvests, fertility of the land, and health for the family. Some songs address the hosts directly, praising their household and expressing hopes for prosperity. The ritual function of these carols is to purify the community and bring divine blessing to each home, linking the sacred to everyday life.

From a social perspective, the ceata de colindători reinforces community ties. Participation in a ceată was traditionally a way for young men to demonstrate responsibility, strength, and cultural knowledge. It was also an initiation rite into adulthood, since the group demanded discipline, respect for tradition, and collective effort. In rural areas, the anticipation of the colindători created a festive atmosphere, as villagers prepared food and drink to welcome them.

Today, the tradition of the ceata de colindători is preserved in many parts of Romania and Moldova, although in urban areas it has been adapted. Folk ensembles and cultural organizations perform carols on stage, keeping the songs alive for younger generations. UNESCO has recognized Romanian carol traditions as part of the world’s intangible cultural heritage, underlining their importance in preserving cultural identity.

CETERAȘ

The ceteraș (folk violinist) is a key figure in Romanian traditional music, particularly in rural communities where live performance has always accompanied celebrations, rituals, and communal gatherings. The term comes from ceteră (violin), an instrument that has been central to Romanian folk ensembles for centuries. A ceteraș is more than a musician; he is a cultural transmitter, preserving and performing melodies that reflect local identity, emotions, and social values.

In many regions, especially in Transylvania and Maramureș, the ceteraș holds a prestigious role at weddings, baptisms, and village festivals. Together with other lăutari (folk musicians), he provides the rhythmic and melodic foundation for dances such as the horă (circle dance), sârba (fast-paced folk dance), or brâul (belt dance). His violin playing guides the dancers, creating an energetic atmosphere where music and movement merge into a collective expression of joy.

The repertoire of the ceteraș includes both ritual and entertainment pieces. Certain melodies are linked to specific moments in life-cycle events. For example, at weddings, the ceteraș plays tunes for the bride’s preparation, the ceremonial departure from her home, and the dance of the guests. At funerals, slow and solemn pieces may accompany the procession, reflecting the community’s grief. These variations highlight the adaptability of the ceteraș to different emotional contexts.

Traditionally, the skills of a ceteraș were passed down orally, with young musicians learning directly from older masters. Improvisation and personal style are important features, allowing each violinist to add unique flourishes while respecting the traditional structure of a melody. This oral tradition has preserved regional diversity, so that one can recognize the style of a ceteraș from Maramureș as distinct from one in Oltenia or Moldavia.

Socially, the ceteraș was both respected and closely tied to village life. In some cases, he was also part of professional groups of lăutari, who performed not only in their community but also traveled to nearby towns and fairs. Their music ensured continuity of oral traditions, as lyrics, dances, and stories were transmitted alongside melodies. Today, the role of the ceteraș continues, though in new forms. Professional folk ensembles, cultural institutions, and music festivals highlight the artistry of violinists who specialize in traditional repertoire.

COLAC

The colac (festive bread) is a traditional element of Romanian cuisine and ritual life, present at weddings, funerals, and major holidays. Made from wheat flour and shaped into a round or braided form, the colac symbolizes eternity, unity, and the cycle of life. Its round shape reflects continuity, while its presence at key moments in a person’s life underlines its deep cultural significance.

At weddings, the colac is offered to guests and often used in symbolic rituals. The bride and groom may break a colac together, signifying unity and shared destiny. During funerals, the colac plays a role in commemorating the deceased, being shared among participants as a gesture of remembrance and blessing. At Christmas and Easter, families prepare colaci as part of festive meals, sometimes decorated with crosses or intricate braids.

The preparation of the colac is linked to ritual purity. Traditionally, women baked colaci with great care, often while observing specific customs such as silence or prayer. Ingredients such as wheat, water, yeast, and salt were seen not only as nourishment but as symbolic elements. In some areas, honey, walnuts, or poppy seeds were added, enriching the flavor and meaning. The act of giving colaci to carolers or guests expressed ospitalitate (hospitality) and dăruință (generosity).

The colac also appears in folkloric customs. During the colindă (caroling) season, children and young people receive colaci from households as rewards for bringing blessings through song. In certain villages, the colac is tied to the ceata de colindători (group of carol singers), emphasizing the bond between ritual food and communal celebration. At harvest festivals, round colaci were offered as thanks for abundance and protection of future crops.

Linguistically, the word colac carries symbolic weight, appearing in proverbs and expressions. Phrases like “îi dai colac la nevoie” (you give bread in time of need) underline its role as a symbol of help and solidarity. Its significance extends beyond food, representing shared culture and social cohesion.

Today, the colac remains a vital tradition, preserved in both rural and urban contexts. Bakers reproduce traditional shapes for holidays, while families continue to prepare colaci at home. The bread is displayed in museums of ethnography as an example of ritual food and intangible heritage.

CRĂCIUN

Crăciun (Christmas) is one of the most important celebrations in Romania, marked by a combination of Orthodox Christian practices and rich folk traditions. Taking place on December 25, it commemorates the Nașterea Domnului (Birth of the Lord), while also reflecting pre-Christian customs tied to the winter solstice and the renewal of nature. The celebration of Crăciun is both a religious holiday and a cultural event that brings families and communities together.

Religious observance begins with the postul Crăciunului (Christmas fast), a 40-day period of abstinence from meat, dairy, and certain foods, emphasizing purification and preparation. On Christmas Eve, known as Ajunul Crăciunului (Christmas Eve), Romanians attend church services and participate in rituals such as the blessing of the colaci (festive bread) and the preparation of meals for the feast. The liturgical centerpiece is the Sfânta Liturghie (Holy Liturgy), celebrated on December 25, which marks the joy of Christ’s birth.

Equally central to Crăciun are folk traditions. Groups of children and young people form a ceată de colindători (group of carolers), singing colinde (carols) from house to house. The songs mix religious themes with wishes for prosperity, health, and abundance. In exchange, the carolers receive colaci, apples, walnuts, or small gifts. In some regions, ritual dances such as the jocul măștilor (masked dance) are performed, using animal masks to symbolize fertility, protection, and the cycle of life.

The culinary dimension of Crăciun is equally significant. Traditional dishes include sarmale (cabbage rolls), cozonac (sweet bread with nuts and raisins), piftie (meat jelly), and roasted pork, reflecting the communal preparation of food and the sharing of abundance. Pork plays a special role due to the custom of tăiatul porcului (pig slaughtering), performed on December 20, which has both practical and ritual significance in rural areas.

Crăciun is a time for family reunions, gift-giving, and reinforcing social ties. The expression to remember is “Crăciun fericit” (Merry Christmas)! While urban celebrations often resemble international Christmas customs, rural areas maintain older rituals, preserving the unique identity of Romanian Crăciun.

EXPAND YOUR KNOWLEDGE

If you are interested in learning more about Romanian culture and history as well as the language, we recommend that you download our complete Romanian language course!

You will not only receive all the contents available on our website in convenient pdf or epub formats but also additional contents, including bonus vocabulary, more grammar structures and exclusive cultural insights with additional vocabulary that you won't in any other textbook.

The additional articles include specific words or expressions related to the culture of the Romanian and Moldovan people. Not only will you be able to speak the Romanian language with confidence but you will amaze your listeners thanks to your knowledge of their country and history.